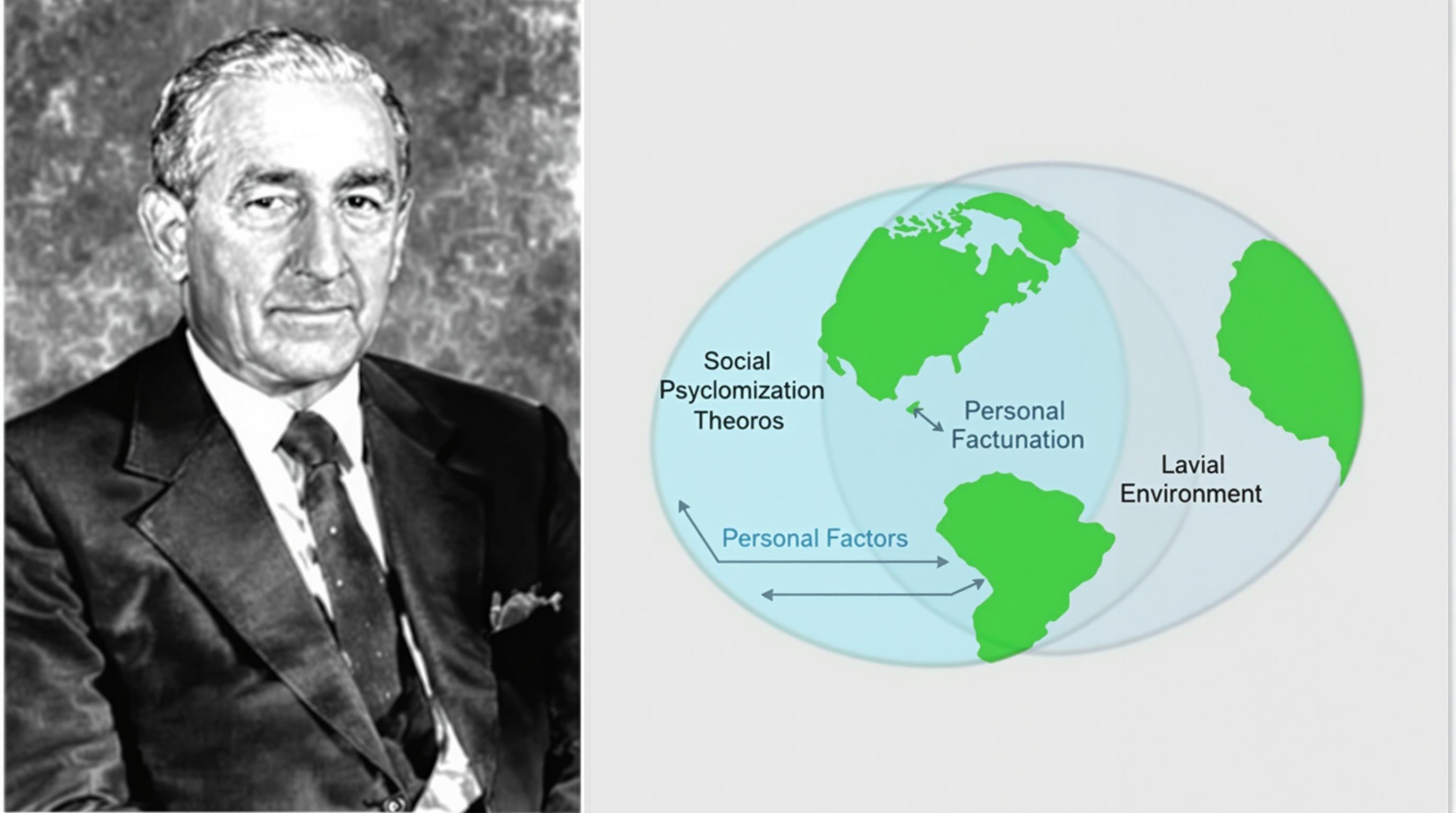

Reciprocal determinism, a core principle of psychologist Albert Bandura's social cognitive theory, explains that human behavior results from a continuous, dynamic interaction between personal factors, behavior, and the environment. The main idea can be succinctly summarized as follows: “A person’s behavior both influences and is influenced by personal factors and the social environment.” This concept emphasizes the ongoing feedback loop where each element shapes and is shaped by the others—providing a comprehensive framework for understanding how people learn and adapt.

At the heart of reciprocal determinism lies the idea that human behavior is not determined by a single factor, but rather shaped through the dynamic and continuous interaction of three core components: behavior, personal factors (such as cognitive processes, beliefs, and attitudes), and the environment. This triadic model was introduced by psychologist Albert Bandura and serves as a foundational principle in social cognitive theory.

The core statement that summarizes the main idea of reciprocal determinism is:

“A person’s behavior both influences and is influenced by personal factors and the social environment.”

This concise formulation captures the bidirectional—and in fact, tri-directional—nature of influence among the three components. Each element does not act in isolation but is interdependent, creating a feedback loop that continually shapes and reshapes human behavior.

Behavior can alter the environment by eliciting certain reactions from others or by changing the physical or social context. For example, a student who consistently participates in class discussions may influence the teacher's engagement and classroom dynamics. Conversely, the environment—such as a supportive teacher or a collaborative classroom—can encourage or discourage student participation.

Personal factors, including beliefs, expectations, emotions, and past experiences, shape how individuals perceive and respond to their environment. These internal factors also guide behavioral choices. For instance, a person with high self-efficacy (belief in their ability to succeed) is more likely to take on challenging tasks, which in turn may lead to successful outcomes that reinforce their beliefs.

Similarly, the environment can shape personal factors. Repeated exposure to failure or success in a given context can alter a person’s confidence, motivation, and expectations. These shifts then influence future behavior, creating an ongoing cycle.

The essence of reciprocal determinism is its circular causality. Unlike linear models of behavior that suggest a one-way cause-and-effect relationship, reciprocal determinism emphasizes a continuous loop of interactions. A change in one component inevitably leads to changes in the others. This model allows for a nuanced understanding of how people adapt, learn, and evolve in various contexts.

Albert Bandura introduced reciprocal determinism as a core principle of his social cognitive theory. His famous Bobo doll experiments demonstrated how observational learning, influenced by both environmental models and personal interpretation, contributes to aggressive behavior in children. These findings reinforced the idea that behavior, cognition, and environment are interlinked.

Further research has validated this model across diverse settings—from educational environments to clinical therapies—highlighting its applicability in real-world scenarios. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) utilizes the principles of reciprocal determinism by addressing thoughts (personal factors) and behaviors to modify emotional responses and improve environmental interactions.

In essence, reciprocal determinism argues that:

Understanding this core statement empowers individuals and professionals to consider multiple dimensions when analyzing behavior and implementing change strategies in educational, therapeutic, or social contexts.

Reciprocal determinism, a concept introduced by psychologist Albert Bandura, emphasizes how human behavior is shaped through a continuous interplay among three key components: behavior, personal factors (including cognitive processes), and environment. Each of these components influences and is influenced by the others, creating a dynamic system that governs how individuals interact with the world around them.

Behavior refers to the observable actions and reactions of an individual. In the framework of reciprocal determinism, behavior is both a product of and a contributor to the ongoing interaction between internal personal factors and external environmental influences.

Personal factors encompass the internal cognitive, emotional, and biological processes that influence behavior. Bandura emphasized that individuals are not passive recipients of environmental stimuli; rather, they interpret and react to situations through their mental frameworks.

The environment includes all external factors that can affect an individual’s behavior and mental processes. This encompasses both the physical surroundings and the social context in which an individual operates.

The essence of reciprocal determinism lies in its cyclical nature. Behavior affects and is affected by both personal and environmental factors. For example, a person’s decision to join a study group (behavior) may be driven by their belief in collaborative learning (personal factor) and the availability of a quiet study area (environmental factor). Once in the group, the interaction with peers (environment) may further influence the individual’s confidence and study habits (personal factors), reinforcing or altering future behavior.

This continuous feedback loop captures the complexity of human behavior, where no single factor operates in isolation. Instead, the dynamic interactions among behavior, personal cognition, and environmental context create a system of mutual influence that shapes how individuals act and grow over time.

Reciprocal determinism, a central tenet in Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory, emphasizes the dynamic, bidirectional interaction between individual behavior and environmental factors. This interaction suggests that individuals are both products and producers of their environments. For example, a student who consistently participates in class discussions may influence the classroom environment to become more interactive, which in turn reinforces the student’s behavior through positive feedback and increased engagement.

This mutual influence is not static; it evolves over time. As behaviors change, so too do environmental responses, creating a continuous loop of influence. This concept is particularly relevant in educational and organizational settings, where behavioral changes can lead to shifts in group dynamics, rules, and cultural norms.

Personal cognitive factors—such as beliefs, expectations, and attitudes—play a critical role in shaping behavior. According to Bandura, individuals interpret their environments through these cognitive lenses, which then influence how they choose to act. For instance, a person who believes they are capable of mastering a new skill (self-efficacy) is more likely to engage in learning opportunities and persist in the face of challenges.

This cognitive-behavioral relationship is reciprocal: as individuals act on their beliefs and observe their outcomes, their thoughts and expectations can evolve. Success reinforces positive self-perceptions, while failure may prompt a reassessment of strategies or beliefs. This feedback loop underscores the importance of mindset in behavioral development and adaptation.

The environment does not only respond to behavior; it also shapes thought processes. Social norms, cultural expectations, and situational variables can significantly influence individual cognition. For example, growing up in a supportive, academically focused household can cultivate beliefs in the value of education and personal effort. Conversely, exposure to negative or limiting environments can distort self-perceptions and reduce motivation.

Bandura’s concept of observational learning further illustrates this point. Individuals, especially children, acquire new behaviors and internalize social norms by observing others within their environment. This learning mechanism demonstrates that the environment actively contributes to cognitive development, which then influences future behavior.

The essence of reciprocal determinism lies in its ongoing, interactive feedback loop. Behavior, environment, and cognition are constantly influencing and being influenced by one another. This triadic reciprocality means that no single element operates in isolation. Instead, human functioning is the result of complex, dynamic interactions among these three components.

For instance, a person experiencing workplace stress (environment) may begin to feel anxious and doubt their abilities (cognition), leading to decreased productivity (behavior). This reduced productivity could then provoke negative feedback from supervisors (environment), further impacting the individual’s self-efficacy and behavior. Understanding this loop allows for more effective interventions in areas such as mental health, education, and personal development, as it highlights multiple entry points for change.

Recognizing the interactive relationships among behavior, cognition, and environment enables professionals to design more holistic interventions. In therapy, for example, cognitive-behavioral approaches aim to alter thought patterns to influence behavior and thereby change environmental outcomes. In education, creating supportive learning environments can foster positive cognitive and behavioral development in students.

Ultimately, the interactive nature of reciprocal determinism highlights the importance of viewing human behavior through a multifaceted lens. By acknowledging the constant interplay between internal and external factors, individuals and professionals can better understand behavior and implement strategies that promote positive change.

To deepen comprehension of reciprocal determinism, it is helpful to explore how the theory plays out in real-world situations. Albert Bandura, the psychologist who formulated this concept, emphasized the dynamic and reciprocal interaction between personal factors, behavior, and environmental influences. Here are some practical examples:

Educational Setting: A student who believes they are capable (personal factor) may study harder (behavior) and subsequently receive positive feedback from teachers (environment). This feedback then reinforces the student’s belief in their academic ability, illustrating the three-way interaction.

Workplace Environment: An employee with a proactive personality (personal factor) might seek out challenges (behavior), which then leads to increased recognition and leadership opportunities (environment). This recognition may further increase confidence and encourage continued proactive behavior.

Social Interactions: A person who is socially anxious (personal factor) may avoid social gatherings (behavior), resulting in fewer social opportunities (environment). This limited exposure can reinforce the person's anxiety, perpetuating the cycle.

Therapists often use the principles of reciprocal determinism to help clients understand how changing one element—thoughts, behaviors, or environmental factors—can influence the others:

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT is grounded in the idea that modifying thought patterns (cognition) can alter behaviors and reshape environmental responses. For example, helping a client reframe negative beliefs may encourage healthier behaviors and improve their social interactions.

Behavioral Activation: In cases of depression, therapists may encourage clients to engage in enjoyable or meaningful activities (behavior), which can lead to improved mood (personal factor) and more positive feedback from others (environment).

Teachers can apply reciprocal determinism by fostering classroom environments that support both behavioral and cognitive development:

Positive Reinforcement: Encouraging desired behaviors through rewards or positive feedback can shape classroom culture (environment) and boost student self-efficacy (personal factor).

Collaborative Learning: Group work not only changes the environment by introducing social dynamics but also influences student attitudes toward learning and participation.

In personal development and coaching, reciprocal determinism is used to design strategies for behavior change:

Goal Setting: Setting specific goals (personal factor) motivates action (behavior), and achieving incremental success can lead to environmental changes such as recognition or rewards.

Habit Formation: Creating a supportive environment—like removing distractions or adding reminders—can help reinforce new behaviors, which in turn can shift self-perception and motivation.

Reciprocal determinism is more than a theoretical construct; it is a practical framework for understanding and influencing behavior. Whether in therapy, education, or everyday life, recognizing the interplay between thoughts, actions, and surroundings can empower individuals to make intentional changes that lead to positive outcomes. By targeting any one of the three components—behavior, environment, or personal factors—individuals can initiate a ripple effect that transforms the entire system.

Effectively assessing understanding is crucial when studying complex psychological concepts such as reciprocal determinism. This section outlines practical approaches to evaluate comprehension, ensuring learners can not only recall definitions but also apply the concept in real-world scenarios.

To assess the learner’s grasp of reciprocal determinism, structured knowledge checks can be implemented. These may include:

These assessments focus on both factual recall and conceptual clarity, encouraging learners to think critically about how the components interact.

Applying knowledge to hypothetical or real-life situations is a potent way to assess deeper understanding. Learners can be presented with scenarios and asked to identify and explain:

For example, a scenario might describe a student struggling with public speaking, prompting analysis of how their self-efficacy (personal factor), classroom dynamics (environment), and avoidance behavior interact.

Encouraging learners to reflect on their own experiences can reinforce understanding of reciprocal determinism. Sample prompts include:

These exercises promote metacognition and help internalize the concept through personal relevance.

Concept maps are visual tools that allow learners to illustrate the interplay between behavior, cognition, and environment. Through this method, students can:

Educators can assess the accuracy and completeness of these maps to gauge conceptual integration.

Engaging in peer discussions enhances comprehension through shared perspectives. Instructors can assess understanding by observing:

This method fosters collaborative learning while providing insight into individual and collective understanding.

To ensure consistent and objective assessment, rubrics can be employed. Criteria may include:

Rubrics provide transparent expectations and guide learners toward comprehensive mastery.

Assessment tools should align with core learning objectives, such as:

By aligning assessments with these goals, educators can ensure that evaluations are purposeful and targeted.

Assessment should not exist in isolation but be integrated into a broader learning and review framework. Techniques include:

These strategies ensure assessments are part of an ongoing process of learning and development.

Understanding reciprocal determinism equips individuals with a powerful lens to comprehend and influence behavior. Recognizing the feedback loop between personal beliefs, actions, and surroundings allows for more thoughtful decision-making in education, therapy, and everyday life. Whether you're a student, teacher, therapist, or simply someone looking to improve personal habits, remembering that “behavior, personal factors, and environment all influence one another” offers a starting point for meaningful change. Take action by observing how your thoughts, behaviors, and surroundings are affecting one another—and consider how small shifts in one area can lead to transformative outcomes.